Also: yes, I think skipping is valuable. Not a valuable skill in itself, but a good way to train jumping mechanics, light-footedness– if this sounds non-technical, try fighting guys who skip and then ones who don’t – and, to some extent, coordination. You should learn it to do it, and preferably to a decent standard.

But, all of that said, I think practising double-unders is a bit of a waste of time.

You might be familiar with Dan Gable, one of the greatest wrestlers (and wrestling coaches) of all time, who once said:

‘If it’s important, do it every day. If it isn’t, don’t do it at all.’

This is where I am on a lot of technical movements that people practice for the gym. Are they fun? Yeah, maybe. Are they important? Not really. Are they more important than other physical skills you could be learning/improving/perfecting, given the same time and environment and commitment to improving your life? Absolutely not.

Here are six things that will absolutely offer more value to your life than constantly practising double-unders. In a way, they’re all a bit like double-unders: easy enough to learn in a couple of weeks’ serious practice, but the sorts of things that you could spend years practising without ever fully mastering. Things that you don’t need much more than a bit of empty space (and a bit of commitment) to work on. Things that will make you fitter, happier, and more competent at life.

1. Breakfalling

I’ve talked about this before, but learning to fall over is one of the most proactive things you can do to reduce your own chances of death by misadventure. Imagine you’re flying off a motorbike right now: are you instinctively forming the correct arm position to not break all the bones in your face? If not, that might be worth working on a bit more than skipping.

2. Punching

Real talk: if you can do more than 10 double-unders in a row but you don’t know how to throw a decent jab and right cross, your priorities are simply wrong. Being able to punch properly is what sets us apart from animals (except kangaroos): a glorious expression of full-body coordination that, when done on a decent bag, feels really, really satisfying. Start with a jab and cross: clean, straight punches that boxers work on for years (and that can get you out of a lot of trouble). Even if you never move on from there, at least you won’t embarrass yourself on the gym’s heavy bag.

3. Climb-ups

This could have said ‘parkour’, but let’s keep things simple: climbing onto a thing is a fundamental human skill, and one that offers an enormous amount of gradation. If you’ve got a wall to hand, do them during training sessions. If not, improvise with a plyo box (your bare minimum: dips on the box). Also, for the love of all that is holy start doing strict muscle-ups on a bar.

4. Swimming

Full disclosure: I am terrible at swimming. I can move forward without drowning, but the intricacies of breathing properly and actually being efficient are (currently) lost on me. I’m working on it, though, since not dying if I fall off a boat is quite important to me.

5. Tumbling

Not the same as breakfalling. We’ll dance over the problems with having ‘handstand walk’ as a key metric of fitness (TL;DR: it encourages you to put unnecessary pressure on your cervical spine) and say, instead, that rather than focusing on getting more mileage on your hands, it’s probably a good idea to work on getting your body upside down in other ways. Learning to cartwheel, macaco, roundoff and otherwise move your body through space in non-common configurations will improve your proprioception, make you happy, and let you show off in front of children and romantic partners. Why would you NOT?

6. Dancing

Look, if you want to throw a CrossFit-themed wedding then all power to you, but just be aware that a) All the other CrossFitters will be judging your form and b) Everyone else will be wondering why you’re doing kettlebell swings instead of a first dance. To put it another way, being able to throw fucking down on a dancefloor is one of the most important, empowering skills a human being can acquire – one that will serve you well and bring you happiness at practically any age. Or to put it yet another way: stop laughing at those people doing the Zumba classes while you do your three sets of squats.

HOMEWORK: Pick one of these things and practise it for at least five minutes, three days this week.

]]>Plan A: Espresso + Iron Maiden

At 5:30am, it’s easy to forget that I basically love the gym, and sometimes all I need to remind me is a double-shot from Pret and a blast of Run To The Hills. If this combination (you may substitute another caffeinated drink + band) doesn’t work, then it’s okay to start thinking that the situation is dire.

Plan B: The World’s Best 2-Minute Warmup

Not what you want to do every day, but golden when you’re half asleep or ruined from work. The protocol:

1A: Skip for 60 seconds

1B: Do five box jumps

1C: Hang from a bar for 20-30 seconds (optional: do 8-10 scapular pull-ups while you’re there)

I’ve stolen (and adapted) this one from Chad Waterbury, who notes that the skipping wakes up your nervous system, while the hang will “open the intervertebral space in your spinal column to free up nerve transmissions to your muscles.” Chad suggests jump squats or running for 1B, but a) It’s tricky to do an all-out 10-second run in most gyms and b) You cannot half-ass a box jump. If this doesn’t get me ready to go, things are bad. So…

Plan C: Just do one thing well

I’ve had some great workouts (and actually some PBs) this way. Essentially, I abandon whatever the ‘planned’ session is, in favour of one (much shorter, so easier to get hyped for) thing – and preferably, a thing I know I should be doing more of anyway. A bunch of pressups or pullups or kettlebell swings every minute on the minute is an option, but so is just doing a big warmup and going absolutely balls-out on a 500m row. Of course, if I can’t even face that…

Plan D: Experiment with training ideas

I have plenty of workout ideas that I want to test out, but I’m loathe to use them on ‘good’ training days. For instance, is previously discussed, I’m a big fan of EMOM workouts, but they can take a bit of finessing to get right: and it’s likely that whatever you’ve seen on some other athlete/gym’s Twitter feed is either too hard or too easy. For instance, here’s a favourite of mine:

Every 30 seconds, for 15 minutes, alternate between:

1A: 4 ring pullups

1B: 6 ring dips

1C: 8 pistol squats

…but that might be too hard or easy for you, either because it’s too much cardio or you hit muscular failure too fast or just not challenging enough. I found out that going harder was a bad idea by trying it on a 5,7,10 rep schemed that flamed out very badly around six minutes in: I’ll probably get there in a few weeks, but for now the above plan is what lets me get the most work done, in the least time. So if I know I’m not going to have a good session anyway, I’ll try out some new ideas. Still too much? Well then…

Plan E: Work on skills

Assuming my CNS isn’t completely shot to shit, working on skills (with nothing in the way of prescribed sets/rest/volume) is a much easier thing to get hyped about than a workout I know I’m going to do badly. Even a few minutes of handstands, laches, kong vaults or whatever is money in the bank for later…and quite often it gets me geared up enough to try something tougher.

Plan F: Get changed, do some mobility, shower, leave

If you don’t get anything else from this post, remember this: building and keeping the habit of going to the gym is the hardest thing about getting in shape. Yes, if you want serious results then the training will be hard, but if you just want to get a bit fitter, feel a bit better and die a bit later (maybe), then just going is the thing you need to worry about. However you feel, however little you want to train, just go. Stretch a bit, don’t worry about training, have a nice longer shower, go. You’ll do better next time: and by keeping the habit, you’ll make sure there is a next time.

HOMEWORK: Train three times this week. Do some of this stuff if you can’t face it.

]]>

But anyway. Beyond being a powerful motivational tool in themselves, the Rocky films make another important point about training: there are lots of ways to do it. So which one should you train like? Easy: the one you aren’t training like already. Each man has certain characteristics that should be part of any training plan, but each also has their flaws.

Here’s how it breaks down.

Rocky

Ah, Rocky. Hard worker, giver of amazing off-the-cuff speeches, lover of robot toys. The message of the Rocky films is a fine one – hard work beats talent – even if, strictly speaking, just getting really jacked is no substitute for actually learning to box. But anyway: Rocky is the epitome of the high-intensity grinder. He doesn’t periodise, he probably doesn’t work off percentages of his training max, he doesn’t think reps are a guarantee of a good workout, he doesn’t factor in rest days – he just goes out and trains his all-American balls off.

Try training like him if…You always go by what’s written in your workout plan, or you only train with intensity that’s ‘measurable.’ You might be overthinking your capacity for overtraining – maybe piling more good, honest, hard work in is actually what you need to bust through a plateau, whether that plateau is mental or physical. And some things are simply not measurable – like smashing a tyre with a sledgehammer or going all-out on the battling ropes or throwing a medicine ball as hard as you fucking can. These are still worthwhile training tools, though, and well worth trying your best on. Train yourself to put forth your maximum effort when there’s nobody around to count reps, and you’ll do better at anything.

Apollo Creed

Poor old Apollo: gets a kicking in every single appearance, and his finest moment is running along the beach in a vest. Still, there’s an important lesson for everyone in Rocky III: sometimes, you need to enlist other people. Specifically, you should occasionally train with other people for two key reasons: they’ll make you do the stuff you hate doing, and they’ll make you do it harder, faster, and for longer, than you’d ever do it alone. Deep in your heart, you *know* there’s stuff you should be doing – sprints, perhaps, or skipping, or learning to throw a jab, or doing proper warmups or more mobility work or long cardio recovery efforts or eating better – but, for whatever reason, you won’t do it. Or maybe you should just work harder than you can manage on your own.

Train like him if…You always train alone. Sometimes you should find someone who’ll do your programming for you, because they will make you do the stuff you hate but need. Personally, my wife keeps me honest about including single-leg work and hamstring assistance exercise in my programme – if she didn’t, I’d never do them. Similarly, I’ll occasionally go to the gym with work colleagues so that I *have* to do whatever workout I’ve planned. You can’t give up 12 minutes into a 5k row race when there’s another guy going just as fast as you. And you damn sure can’t let them win.

Clubber Lang

The polar opposite of the Creed approach, and an appropriate role model for anyone who needs a roomful of high-fives and 15 Facebook Likes before they think they’ve had a decent workout. In the words of the man himself: ‘I live alone. I train alone. I’ll win the title alone.’ That’s some serious self-belief from a man whose idea of training for a world title fight is doing wide-grip pullups in his cellar.

Train like him if… You normally have to train with other people – a PT, a class, or friends. This is obvious, but you should also train like Clubber if your pre-workout ritual is too elaborate: this describes you if you’ve ever said you can’t lift without your favourite music or your favourite bar/shoes/skipping rope. If you ever have to fight or run for your life, it probably won’t happen with your carefully-selected Metallica playlist running, so maybe occasionally you should train with whatever shitty Euro-trance your gym plays as a distraction. You know what Clubber Lang would do if his pullup bar didn’t have the right knurling? He would do pullups until it broke, snarling expletives at it all the time.

Ivan Drago

Ah, the Russian. Drago is the perfect example of Eastern-bloc efficiency, not just because he has a special running track with speedbags mounted on it, but because everything he does is pre-planned by Bridgitte Nielson and her team of sinister scientists. Measurable, well-planned training programmes work, and will occasionally allow you to punch another man’s head almost clean off.

Train like him if….You eschew any kind of planned training in favour of winging it and attacking every workout like a madman. Intensity works, but it doesn’t work as well as planned progression, with planned recovery workouts and phases of overreaching. If you’ve never followed a proper training plan, this is you: get on Starting Strength, or 531 or Greyskull, or something similarly sensible – but stop just throwing shit at a wall. Maybe get someone else to write you a programme. Maybe write your own. But if you don’t know how you’re going to train for the next month, you should work it out. And then attack those workouts like the entire politburo is watching them.

Adonis Johnson

Your last resort. At the start of Creed (minor spoilers incoming), Adonis Johnson is taking things a little bit too easily, effortless smashing up lesser fighters before he gets a fist-shaped lesson from the gloves of real-life world champ Andre Ward. Predictably, this lights a fire under his well-tailored fight-shorts, and six months later he’s training with Rocky Balboa to take on the light heavyweight champ of the world. The timespan’s truncated, sure, but the theory is sound.

Train like him if…Your training plan needs a kick in the ass. If you’ve been winging it recently, or just coasting through workouts, then sign up for a fight, marathon, obstacle race, strongman competition, or whatever else you need to guarantee yourself public humiliation and pain if you don’t suck it up and start taking things seriously.

HOMEWORK: Work out which one of these fits you and get it in place. To recap: Balboa if you haven’t gone balls-to-the-wall in a while, Creed if you always train alone, Lang if you never train alone, and Drago if you need some programming. Get it done.

*In case you’re wondering, the Rocky films, ordered best to worst, go 3,4, Creed, Balboa,1,2,5. Don’t bother arguing: this isn’t a democracy, and you’re wrong anyway.

]]>

‘I’m probably the weakest person here. But I’m going to show them that it’s all about willpower.’

Gah.

Okay: possibly, if you think about that for under three seconds, it sounds fine, even laudable. Yeah! It’s not about strength at all! It’s about grit, and determination, and all those other things that special forces talk about! Show them, buddy! Show them all!

But here’s the problem with this: everyone has willpower. It’s not just a secret weapon reserved for the weak. The question is, how much do you want to rely on yours?

Sometimes a thing seems obvious, but I’m going to say this anyway: if you have to start relying on willpower after 5 pressups, you are probably going to come up short against the guy who can do 50 before his arms start to hurt. If you’re chugging through your willpower reserves to maintain a nine-minute mile pace, you’re going to fade before a guy who can do eights all day. If you need willpower to get through a 10km run, you’re going to run out of it a hell of a lot faster than the guy who calls that a recovery day. Willpower, it’s fairly well-established, is a finite resource: you run through it just like (and possibly in tandem with) your glycogen reserves. You want to hold off using it for emergencies. And if you’re weak and slow, that isn’t an option. Yes, special forces are going to push everyone as far as they can, at some point in their training: but if you’re redlining six hours in, while everyone else is still in third gear, you’re in trouble.

But I’ll go you one further.

Willpower, most recent studies suggest, is a lot like a muscle. It improves when you work on it, by doing hard, uncomfortable tasks that you’d really rather not do. Yes, there are people who seem blessed with a lot, just like some people grow up with a preternaturally high VO2 max – everyone’s met that one untrained guy who’ll walk in off the street and bury himself to beat you in a physical contest he has no earthly business winning – but in general, people who train hard will have more willpower than people who don’t. Doing some hard work makes more hard work manageable. And if you’re the kind of guy who’ll show up to an SAS show without being able to do 100 pressups, how much willpower have you really got, anyway?

So here’s my suggestion: next time you’re planning on tackling something physical, act as if you’ll have no willpower to fall back on. Push your work capacity up as far as you can: with long recovery runs or hundreds of pressups a day, or bodyweight squats or burpees or whatever the hell else you’re going to have to do. You’ll hit the redline later, or you might not hit it at all.

HOMEWORK: Pick an amount of pressups that’s about a third of your strict one-set max, and do it every minute, on the minute, for 20 minutes. Do it again next week, and add a rep. Never let yourself be terrible at pressups again.

]]>- If you are a professional athlete or your life is otherwise dependent on you being in shape, you should be training. This includes anyone shooting for some sort of athletic scholarship, and maybe people who just want to get really good at something – like, internationally-competitive-level good. Your competitive lifespan is (hopefully) going to be relatively short compared to your actual lifespan and the stakes are high, so every workout should be tailored to making you better at The Thing. That means doing exactly the amount of work that will make you optimally good at your sport: not throwing in an arms day every so often because you feel like it. Let’s face it: this probably doesn’t apply to you.

- If you’ve given training a genuine try and you hate it, you should just work out. This is where I part company with a lot of coaches, mainly because I’ve met men and women who are spectacularly good at what they do without ever having followed any sort of training plan. MovNat founder Erwan LeCorre, for instance, and many Parkour guys, will never follow any sort of training plan: they don’t need to, because they work hard and use a sensible variety of movements. This is tough to do though, so my advice is to at least try a few training plans before you swear off them forever, because for most people planned progression is better. Having a few indicator numbers to look for and improve, learning how to balance the basic movements, getting a sense of how to manage work and recovery – these things will make you better in the gym even if you aren’t training for anything specific. But if you hate following programmes, just move around and have some fun. Plenty of people go running or hit the weights three times a week without any sort of plan: they aren’t progressing like they could, but they’re still almost certainly better off than people who don’t go to the gym at all.

- If neither of the above apply, you should train and work out. This is me, and hopefully you, and honestly probably the best choice for most people. I know what my squat, deadlift, pullup max and 5k time are, and I’m usually trying to improve them, but I am usually up for sparring, going for a quick run, a pullup competition, trying some new tricks, having a go at a workout somebody else wants to try or just smashing out some tyre flips because it’s sunny in the car park. If I get the chance to do something fun, I’ll do it before I worry about how it’s going to affect my back squat. If I feel like doing some pressups because I’m watching Arrow and it makes me all aggressive, I’ll do that. Is that optimal for progress? No, but I’m not a professional athlete, so that doesn’t really matter: I’m strong enough that I’ve hit the point of diminishing returns, and life’s too short to think about strict presses the whole time. My advice? Have a few ‘indicator’ exercises and a general programme – three days a week is a good aim – and then do what you like the rest of the time.

Training is a good thing if you’re an athlete. But you probably aren’t an athlete. There’s nothing wrong with just working out once in a while.

]]>

Minute one: do one burpee (let’s get the terminology right: this means chest to the floor at the bottom, get up however you can. The pressup doesn’t need to be strict). Rest for the rest of the minute.

Minute two: do two burpees. Rest for the rest of the minute.

Repeat until failure/collapse.

It’s a format with good points and bad points. ‘Good’ is that you tend to get quite a bit of volume in, because the numbers go up in what’s known as a triangular series, where the last round you hit, n, means you’ve got: n(n+1)/2 reps. Getting to the round of 12 means you’ve done 78 reps, for instance, which is pretty good going. Bonus: you probably don’t need much warmup, because the early reps will get that done. And the best bit is that, if you choose your exercises properly, it always descends into the kind of unrelenting horror where each round becomes a choice between quitting and somehow getting through it, knowing that the next round is going to be even worse. After all, intentionally putting yourself through certain sorts of horrible things is good preparation for life.

The ‘bad’ is that this doesn’t work with everything. Death by pullups, for instance, is a CrossFit staple, but if you aren’t going to do kipping pullups (and there are good reasons not to) then your muscles will fail before your conditioning/heart, which isn’t much of a good test of anything. So death by burpees is great: death by bench press isn’t. Do a Death By workout today: they’re good, kit-free fun.

Still here? Bad news. Inevitably, there is an even worse way to do this.

Once you’ve got the hang of Death By Burpees, the much, much nastier option is this triple-header, devised by Michael Blevins.

Death By Triple Threat

(for each exercise, do 1 on the first minute, 2 on the 2nd minute etc, until you can’t get the required reps in a minute)

ROUND 1: Death By Burpee Pullups (chest to bar)

When you fail, on the next minute go straight into:

ROUND 2: Death By Burpee Box jump (start again at 1)

When you fail, on the next minute go to:

ROUND 3: Death By Burpee (start again at 1)

The ‘good’ thing about this is that it gives you three chances to fail, and some time to recover between them. It’ll keep your heart rate high and test how much you want to carry on, because it only gets worse as you tire. ‘Some people finish this and go ‘Oh, I didn’t really do much work there,’ says Blevins. ‘I’ll go: that’s because you quit.’

To give you an idea of what not quitting would be like, this should go something like 40 minutes long: 11 reps of round one and two, maybe 18 reps of round three. That’s 303 burpees and a lot of unpleasantness.

Death by Burpees. Get to it: and please don’t actually die.

Last year I set my gym-sights on (and barely managed) a 7-minute 2k row, which is considered the minimum acceptable standard among the fine men and women of Gym Jones. This year I’ve been hitting different distances, and managed a borderline-acceptable 10k time (39:46), and an actually-pretty-decent-for-my-weight 500m PB (1:28.6). I’m currently signed up to Concept 2’s Million-Metre Club, and I’m about twenty percent of the way through. I also talk to my wife, half of the trainers at my gym, a few of the people at work, and a bunch of people on Twitter, about stroke rates and damper settings and pacing strategies and split times, basically all the time.

Like I say, I think about it a lot.

The plus side of this is that I also acquire a lot of rowing workouts: whenever someone sends me a new one, I feel honour-bound to try it out, but trying a slightly new ‘thing’ is more fun than doing a 2k/5k/10k every time you crank up the flywheel. With a decent selection of different distances and times to improve on, there’s always something to beat.

So: here’s a selection. The good thing about rowing, as opposed to running, is that there’s basically no adaptation period needed: you aren’t going to get shinsplints or impact injuries by doing too much, too soon. That said, the pacing strategies suggested here are mostly on the ‘hard’ side of things, so if you’re new to rowing/the gym/exercise, downscale them to something that lets you get a decent amount of metres in without blowing yourself out of the water in the first 60 seconds. Real unpleasantness takes time.

#1 Dean Martin

“I feel sorry for people who don’t drink.’ Dean Martin once said. ‘When they wake up in the morning, that’s as good as they’re going to feel all day.” Well, Deano, I drink: and I like doing this workout first thing in the morning, because – unless you get fired or hit by a car or something – it is definitely the worst thing that will happen to you all day. Thanks to the guys of Gym Jones for this: the stupid name is all me, though.

- Row 150m in 30 seconds.

- ‘Rest’ for 90 seconds, but do 10 press-ups and 5 goblet squats (I’d suggest a 24kg dumbbell) during the rest.

- Row 151m in 30 seconds. Rest/pressup/squat again, then row 152m, and so on…until you can’t get the required metres.

The ‘strict’ version of this requires that you just do more metres in each interval, which takes concentration and gets bad quickly if you accidentally hit a 156 early thanks to overzealous pulling. If you’re unused to pacing, just aim to hit the required, and gut it out through at least 15 rounds – if you’re very light or deconditioned, start at 140.

#2 Tabatas

Most people, as previously discussed, get Tabatas completely wrong: doing 20 seconds on, 10 seconds off, for 8 rounds, is not a Tabata, however much you might wish it was. However, they work pretty well in any format where you can thrash yourself to death for 20 seconds and then barely recover. Advantage: rowing.

- Row all-out for 20 seconds.

- ‘Rest’ for 10 seconds.

- Repeat 8 times.

There are two ways to do this: either ‘pace’ it by aiming for a minimum distance per interval (100m is sensible), or just go all-out, every single time. They’re both pretty bad.

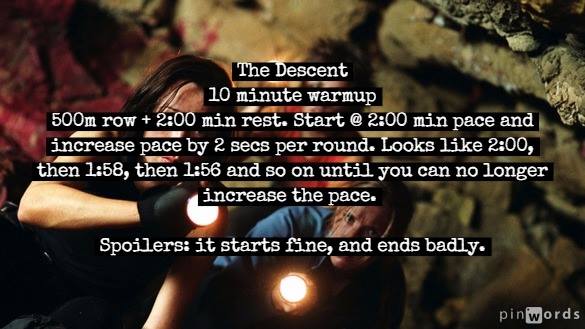

#3 The Descent

This comes via the excellent George Mayhew, who is almost definitely a better rower than me. I’ve called it The Descent because, much like the 2005 film, it starts out pleasantly enough, gets very nasty surprisingly quickly and ends in absolute horror. Here goes:

- Row 500m in 2:00m

- Rest for 2 minutes.

- Row 500m in 1:58. Rest 2 min. Keep going, dropping by 2 seconds each interval: 1:56, 1:54…until you can’t make the cutoff. Getting into the 1:40s is a good target – the round of 1:34 is impressive stuff.

#4 The Descent 2

Michael Blevins suggested this one: it’s very much like The Descent, except that it turns bad faster and leaves you more broken.

- Row 500m in 2:00m

- ‘Rest’ for 2 minutes – including 5 pressups.

- Row 500m in 1:58. Rest 2 min, including 10 pressups.

- Keep going, dropping by 2 seconds each interval: 1:56 + 15 pressups, 1:54 + 20 pressups…until you can’t make the cutoff. If you make it to round 7, you’ll have done 105 pressups. Keep going.

This is also a good test of balance: if you’re struggling to finish the pressups before the rowing gets hard, you probably need to do more pressups – and vice versa.

#5 Death by 500

- Row 500m in under 1:42

- Rest 2 minutes

- Do as many rounds as possible.

#6 The 2K Predictor

‘Here’s the secret,’ says Pieter Vodden, who sent this my way. ‘The average pace you can hold for these intervals will be what you can hang onto for a 2k. Translation: if you want to hit a sub-7 2k, you need to hold a 1:45. It’s no fun.

- Row 500m

- Rest 1 minute

- Repeat 10 times

#7 Stairway To Heaven

- 1: Row 250M (3 min. rest);

- 2: Row 500M (3 min rests);

- 3: Row 750M (3 min rest);

- 4: Row 1000M (3 min rest);

- 5: Row 1250M (3 min rest);

- 6: Row 1000M (3 min rest);

- 7: Row 750M (3 min rest);

- 8: Row 500M (3 min rests);

- 9: Row 250M (3 min. rest);

- Do it all at your target 2k pace.

#8 The Count

If you want a nice long session that’s not boring and forces you concentrate on pacing, this is the answer. ‘This is a proper rowing workout,’ says George. ‘By which I mean: one by those who actually row in a boat.’ If it’s good enough for them…

10 min row to warm up

Then:

6000m row completed in 500m continuous blocks. Pacing is done by strokes per minute (s/m). Start @ 18s/m for 1st 500m. Then increase pace by 2s/m every 500m to 28s/m, then go back down to 18s/m. Last 500 is done @ 20s/m. Pace stays between 2:00 and 1:50.

0-500m @ 18s/m

500m-1000m @ 20s/m

1000m-1500m @ 22s/m

1500m-2000m @ 24s/m

2000m-2500m @ 26s/m

2500m-3000m @ 28s/m

3000m-3500m @ 26s/m

3500m-4000m @ 24s/m

4000m-4500m @ 22s/m

4500m-5000m @ 20s/m

5000m-5500m @ 18s/m

5500m-6000m @ 20s/m

Cool down row

‘It’s a different experience rowing to strokes per minute rather than the 500m pace indicator,’ says George. ‘You end up pulling a lot harder. The key is to stick rigidly to the given pace.’

#8 Up To Eleven

- 1000m followed by 3min rest +

- 750m followed by 2:30min rest +

- 500m followed by 2min rest +

- 250m followed by 2min rest +

- 750m finish. Record total row time.

BANG. Add those to your regular rows, and you’ll be hitting new PBs in no time. Hit me up on Twitter: I’ll be happy to congratulate you.

]]>

5. Most people aren’t judging you

One of the most common fears among – well, anyone – is that they’re being constantly judged or made fun of by people around them. ‘This is half right,’ points out Neil Strauss, author of The Game. ‘People may notice you, but most of them are too busy worrying about what people are thinking of them to judge you. Once you realise that most people are just like you, you’ll start to become socially fearless.’ PUAs ‘learn’ this by relentlessly approaching groups of girls – you can do it more easily. From now on, when you’re worried about people judging you, just think about how infrequently you worry about what anyone else is doing. That ought to fix it.

4. Some people are just naturally better at X – but that doesn’t matter

Let’s not get into a nature/nurture thing and just accept that, yes, some people seem ‘naturally’ better at talking to members of the opposite sex, just like some people are ‘naturally’ more confident in job interviews, presentations, or BAFTA acceptance ceremonies, or ‘naturally’ better at maths, running fast, or kicking a ball into a net. Maybe they are. But that doesn’t matter, because if you aren’t ‘naturally’ talented, it’s not about who you are – it’s just about what you do and how you present yourself. Fix that – even if you have to fake it at first – and soon (well, at some point) you’ll have people envying your ‘natural’ talent. At this point, you can charge them two thousand pounds for a seminar, or break the cycle by, y’know, acting like an actual human.

3. ‘Being yourself’ is overrated

You’ve been told by dozens of films, cartoon animals and bitter X-Factor exit interviews that ‘being yourself’ is the highest ideal you can aspire to – but is it, really? Yes, it’s great if you’ve got a strong sense of who you are, what your strengths and values are, and how to convey them effectively – but no, it isn’t, if you’re using it as an excuse not to improve. Or, as Strauss has it: ‘What most of us present to the world isn’t necessarily our true self: it’s a combination of years of bad habits and fear-based behaviour. Our real self lies buried underneath all the insecurities and inhibitions. So rather than ‘being yourself’, focus on discovering and permanently bringing to the surface your best self.’ Seems legit.

2. Outcomes aren’t everything

Yes, it’s possible to be too outcome-focused. Life is unpredictable: even if you do everything exactly right, you aren’t always going to get exactly what you want: whether that’s a phone number, a date, a marriage, a specific job, a six-pack or a book deal. Being too outcome-focused, as most PUAs learn, can turn into a form of self-sabotage. Instead, emotionally detaching from the outcome – while taking rational steps towards smaller goals – can keep you focused. It’ll happen sooner or later – the important thing is doing everything you can to get the process right, and not beating yourself up over missteps.

1. ‘Inner game’ is better than ‘game’

At some point, all ‘PUAs’ make a distinction between ‘outer game’ – ie all the pre-prepared lines, routines, magic tricks and general bullshit that most ‘gurus’ teach – and ‘inner game’, which is basically shorthand for ‘being a slightly better person.’ Ultimately, the theory goes, confidence is difficult to fake, and so becoming genuinely more adventurous, curious, sociable and confident is much, much better than pretending. Instead of faking it until you make it, the idea goes, fake it until you become it – an idea which, like all the ones above, goes far, far beyond hitting on ladies in bars.

]]>But let’s assume for a second that we aren’t all going to be dissected at a molecular level by a swarm of nanobots – it’s still starting to look like your zombie survival fitness plan (it’s parkour and pullups, let’s be honest) isn’t going to be enough. Robots are tougher than the living dead, and while DARPA’s terrifying horse-bot may not be much faster than a pack of shamblers now, give it a few years and that thing will be hitting full gallop. The even better news? Training for a robopocalypse will stand you in good stead for almost anything in life, so even if you’ve only got a few sweet years before Roko’s Basilisk destroys us all, you’ll be able to enjoy them better with a well-structured workout plan. Here’s what you need to cover.

- A solid strength-to-weight ratio. This comes above all else. You need to be efficient at moving your own bodyweight – but more importantly, if you get shot in the leg and Linda Hamilton needs to haul you out of a building, you’d better not look like a circus fatman. Also: it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to sustain a 5,000 calorie-a-day (or whatever) diet when you’re on the run, so it’s worth being used to less.

- The ability to do repeated (sub-max) sprints. Also crucial. Being able to run a marathon is probably going to be less important than being able to run away from T1000s very quickly. But don’t get complacent about the long, slow efforts, because you’ll also need…

- Decent long-distance endurance. Think hike, not 10k. This is going to be crucial when we’re all fleeing for the hills, where the less-wheeled robots can’t get us.

- Excellent grip strength and endurance. Hand-to-hand combat isn’t going to be much good against robots: bare minimum you’re going to need a sledgehammer. You’re also going to be mending fences, digging ditches and fixing things.

- Excellent hauling and loading work capacity. Because in a world where every forklift truck is trying to murder you, you’re going to be carrying a lot of stuff around.

Fortunately, as already mentioned, these are also good ways to prepare yourself for life in general, improve your quality of life, and buffer yourself against lots of age-related and cardiovascular diseases. How do you cover them all in one plan? It’s simple, if not easy. Here’s how I’d structure a typical week.

The Robopocalypse Training Plan

Please note: this doesn’t include warmups, structural work or injury-proofing. It is just a guideline. It is not guaranteed to safeguard you against malevolent robots.

Monday

Power clean or deadlift, at 80% of your 1RM. Aim for 5 sets of 3.

100 pullups

200 pressups

Tuesday

20-30 mins sledgehammer swings on tyre. Aim for 10 swings per side, per minute. Go hard.

Sled pushes or loaded carries for 20 minutes. Think farmer’s walk, zercher carry, etc.

Wednesday

Long slow run or (preferably) hike with a weighted vest or backpack. If you haven’t got anywhere to hike, weighted stepups aren’t a bad idea. If you aren’t going to freak out the neighbours or get shot, maybe do this carrying a sledgehammer or other similarly-heavy handheld object.

Thursday

Explosive jumps (box jump or broad jumps) in the warm-up

Front or back squat, at 80% of your 1RM. Aim for 5 sets of 3.

Push-press at 80% of 1RM. Do 4 sets of 4.

1 mile run (all-out) to finish.

Friday

Short medium-paced run – 5k or so.

Saturday

Strongman day: warm up with a 10-minute medley of loaded carries (farmer’s walk, waiter walk, zercher carry, sandbag carry, etc), then play with strongman moves – keg loading, tyre flipping, sled pushing and the like. No strongman kit? Improvise.

Sunday

Long (30-60 minute) recovery-paced effort – either a nice walk or a very slow run. Or just rest. Resting is fine. If you want the robots to get you.

You can knock days out of this, and you should add accessory moves as necessary. Doing more pullups, pressups and grip work is almost always a good idea, and unless you’re a professional level athlete it’s highly unlikely that you need to worry about overtraining. The key – as with life in general – is to get your work capacity up, so that whatever happens, you’ll be vaguely prepared. Oh, and just so you don’t have nightmares, read this excellent Isaac Asimov short story about the future of technology. Maybe you won’t need this stuff after all.

]]>