This year, I made a conscious decision to read more. I always read a lot, but last year – for reasons to do with the dopamine-spiking rush of social media, a hectic schedule, and developing a bad habit of watching films on my commute – things dropped off. Then a friend of mine posted a list of books she read in 2016, and it totally put me to shame. How the hell did she have time for all that reading, I asked myself? Or, more importantly, how didn’t I?

So I decided to read lots. The vague goal was a couple of books a week, which I more-or-less stuck to – I thought about going for an even hundred, but quickly realised I’d end up deliberately reading short, sharp books and skipping the weightier stuff, which ran counter to the whole spirit of the thing. So instead of going for a target number, I just stuck with the principles from this post – which, summarised, are:

- Read everywhere

- Read all the time

- Make reading into a habit

Here’s what I learned, followed by mini-reviews of the full list, followed by my top ten of the year. Yes, this is a long post.

Reading broadly makes reading fast easier

It’s much easier to read lots if you have two books in the clip at once. Sometimes, you’re in no mood for hard science and you need fiction: sometimes, when you’re worn out on fanciful phrasing, you can just speed through some self-help tome that’s spinning out a TED talk into 250 pages. The surprising bonus: this way, you see connections between books and ideas everywhere, in the most unlikely places, until it feels like your brain’s fizzing.

You have to read fiction

I’ve talked to a couple of high-achieving people this year (one ex-special forces, one Olympian), who told me that they don’t read fiction because it’s a waste of time. I respectfully disagree: studies suggest that fiction increases your empathy, and I’d anecdotally argue that literature gives a better handle on the tragedies of human history (and the human psychology behind them) than more dry historical accounts. Also: the sheer buzz of reading pure, well-written fiction beats a whole lot of other legal (and illegal) highs, at least for me.

Science is better when it’s written by scientists

I went to the source for a lot of my science-reading this year, and it makes a huge difference. Most importantly, good scientists are in it for the furthering of human knowledge, which means they’ll admit when there are shortcomings in an argument or aren’t sure something is right: unlike professional writers, who are pretty invested in cherry-picking arguments that support the book they’re selling. Counter-intuitively, this makes them more trustworthy: if one guy goes ‘Evidence is scant for this one thing but we’re pretty sure this other thing is true’, it’s a lot easier to use the information than when a book presents everything as equally valid, equally stone-cold true. Secondly, you get better anecdotes from scientists who’ve amassed them over long careers than the what-I-did-on-my-holidays nonsense you get from journalists (classic example: the Gladwellian trend of telling you about every interview subject’s hair and outfit, in detail). Thirdly, scientists understand science, which is important when you’re talking about science.

I need to read more books by women

There was a point, sometime around October, when I decided to tot up how many books by women I’d read over the year, reasoning that, since I could remember a lot, it was probably at least 40% of the total. This turned out to be availability bias, and stupendously wrong: it was less than 25%, even though those books a) Were some of the very best of the year and b) Gave me a much-needed perspective on a lot of things I hadn’t been thinking about. Yes, I also need to read more by authors from minorities: I couldn’t even kid myself about that one.

The full rundown? Okay, let’s do this. If you’d rather just get the top 10, skip to the bottom.

I read Stephen King’s On Writing near the start of the year, which is both fascinating biography and a kick in the pants for anyone who thinks books should take years to write. Then Into The Woods gave me the superpower of being able to predict the plot of (almost) any book or TV show I ever watch, and also the excellent showoff phrase ‘fractal plot-arcs’. Cheryl Strayed’s Tiny Beautiful Things was a fantastic collection of good advice from a lady I grew to respect more after I also read her memoir Wild, which (alongside Robert Webb’s similarly excellent How Not To Be A Boy) was probably the closest I came to crying at a book all year. After that I recovered with Alan Partridge’s stupid-but-funny Nomad, then John Vaillant’s impeccably researched and beautifully written exploration of environmentalism, survivalists and Russian masculinity The Tiger, which was so good that I immediately bought his logging/ environmentalism/ colonialism primer The Golden Spruce and enjoyed that even more. Oh, and Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search For Meaning was every bit as good as you’ve heard. It’s also short! Read it today.

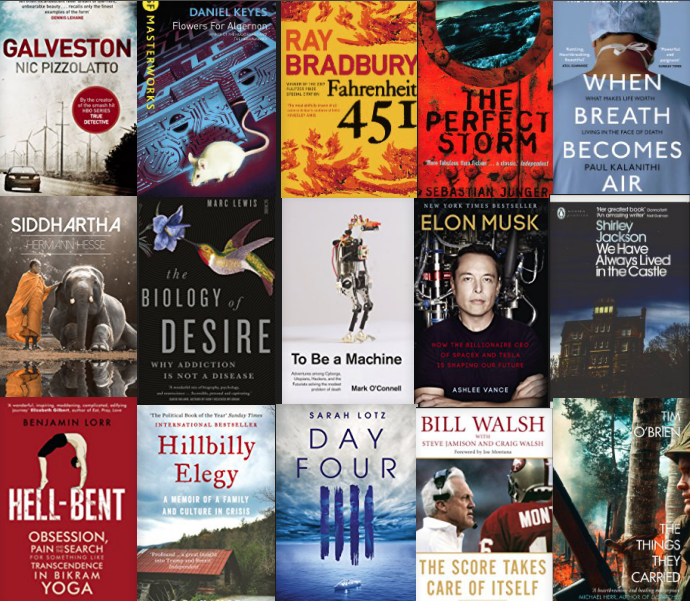

Also early in the year I bashed through Matt Fitzgerald’s pretty good (though not as good as Iron War) How Bad Do You Want It? And then David Halberstam’s The Education Of A Coach, which wasn’t as good as The Score Takes Care Of Itself, though I’d still much rather read about American football than actually watch it. Ed Caesar’s Two Hours was solid – especially in the context of the recent Nike attempt at a sub-2 marathon – but a bit heavy on the anecdotes and light on the science for my liking, which might not be the same as yours.

Unexpectedly, Zia Hayder Rahm’s In Light Of What We Know was a minor clanger – it feels a lot like a collection of nice ideas smashed together with a story that doesn’t quite work – but then I stumbled onto Sebastian Junger’s Tribe and loved the writing so much that I grabbed and devoured War, The Perfect Storm and (later in the year) A Death In Belmont, bringing me entirely up to date with an author I didn’t even know I was missing out on. Junger reminds me a bit of The Corner’s David Simon in his approach to journalism: he plants himself in a corner and starts chatting to people, spends months getting the research right, then tells you a story that explains everything from first principles until you feel like an expert. Just incredible stuff.

I also read enough end-of-the-world books to form their own category, starting with the science-heavy The Knowledge, which made me resolve to learn more science but also left me utterly convinced that the main problem with every single survival scenario is not immediately starving to death. Margaret Atwood’s The Heart Goes Last was the only mild dud, starting out brilliantly with a little-used scenario (economic meltdown), then trailing off into satire with a bunch of set-pieces that felt like they’d been cobbled together from other projects. Seveneves (moon explosion) was classic Neal Stephenson, in that it was a bunch of variably-interesting discourses on engineering, space travel and mad future biology, smashed together into a story that I read really, really fast considering it was 900 pages long. Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven (pandemic) just loses out to Peter Heller’s The Dog Stars (pandemic) for honourable mentions, but the head-and-shoulders winner was Black Wave (environmental catastrophe), which really only uses the scenario as the backdrop to a glorious riot of lesbian culture, memorable similes and smart observations (‘people tended to judge drug abuse unless you were an imposing or hardy man and then they sort of reluctantly envied your daring.’’Michelle seemed more like some sort of compulsively rutting land mammal, a chimera of dog in heat and black widow, a sex fiend that kills its mate.’) In actual how-fucked-is-the-world terms Eric Hoffer’s must-read True Believer was my most-highlighted book of the year, with 78 passages) barely shows its age (typical quote: ‘We do not make people humble and meek when we show them their guilt and cause them to be ashamed of themselves. We are more likely to stir their arrogance and rouse in them a reckless aggressiveness.’) Meanwhile, Will Storr’s Selfie is a fantastic sequel to his also-excellent Heretics: an investigation of the roots of our never-more-narcissistic age that starts at Ancient Greece and ends with Instagram. Oh, and Mark Fisher’s Capitalist Realism is a zippy little number that’ll give you smart things to say about Zizek and a handful of classic films , in case that seems worth a go.

Somewhere in May I suddenly had a newborn baby to deal with, and so I read a whole bunch of American classics in a sleep-deprived fug at 4am, cradling the little chap in my arms. The Things They Carried was haunting and great, Flowers For Algernon more uplifting than advertised and Fahrenheit 451 actually a bit patchy, but with spots of ferociously good writing/insight that make it certainly worth a go. Somewhere in there, medical memoir When Breath Becomes Air left me sort of numb, Shirley Jackson’s We Have Always Lived In The Castle shone with black humour and Syd Moore’s witch-detective-romance Strange Magic was absolutely fine, though also totally missable.

On the borders between science and self-help, Daniel Levitin’s The Organised Mind is a fantastic introduction to the genre, covering actionable tips from almost every field in a tome so comprehensive it’s actually kind of exhausting. Angela Duckworth’s Grit and Gabriele Oetingen’s Rethinking Positive Thinking were both excellent distillations of research conducted by the authors themselves, and so both worth a read, even if the central messages of both (do hard things on purpose/visualise challenges when you set goals) probably don’t demand a book-length read. Peak, written by the man who conceptualised what we now call ‘deliberate practice’ (Anders Ericsson), clarifies a tonne of the misinformation around his theories – including the reason the 10,000 hour ‘rule’ isn’t really a thing, which means that I now automatically mistrust any book that cites it. Unfortunately, that includes Ben Bergeron’s Chasing Excellence, which was an otherwise-okay roundup of mental prep techniques used by pro CrossFit athletes, padded out with a load of descriptions of the games that you’d be better off watching on YouTube – if you’re in the market for sports psychology Steve Magness’s Peak Performance is a solid intro to a whole bunch of good ideas, and generally just better. Meanwhile, Adam Grant’s Originals seemed compelling at the time but I haven’t used anything from it, Ryan Holiday’s The Obstacle Is The Way was a decent mish-mash of anecdotes, Peter Thiel’s Zero To One is too full of survivor-bias bullshit to read with a straight face (one of my Kindle notes just reads ‘wanker’) and Charles Duhigg’s Smarter, Faster, Better was straight-up excellent, though not as life-changing as The Power Of Habit. Best of all, partly because the author used his own advice to become a world champion in his subject matter, was Moonwalking With Einstein, a zippy read through the history of memory with actual insights into how to use the info inside.

Dancing effortlessly into ‘harder’ science, Niels Birbaumer’s Your Brain Knows More Than You Think was a zippy little intro to neuroplasticity which dovetailed nicely with Marc Lewis’s The Biology Of Desire, a fascinating take on why we’re (probably) getting our treatment of addiction all wrong…and led perfectly into Steven Kotler’s Stealing Fire, which has some fascinating stuff to say about the intersection between psychedelics, ‘peak experiences’ and spirituality. Mark O’Connell’s To Be a Machine managed to dawdle its way around a bunch of absolutely fascinating subjects (AI, cryotherapy, life extension) without actually explaining any of them properly, and annoyed so much with its English-professor whimsy that I jumped straight into Nick Bostrom’s bracingly stern Superintelligence, which made me alternately terrified and weirdly buoyant about the possibility of ‘strong’ AI. Semi-relatedly, I also read Ashlee Vance’s biography of Elon Musk, which has just enough insight on the man’s thinking that it’s probably worth a quick blast, though you’re probably going to end up liking Musk less when you’re done. Cordelia Fine’s Delusions Of Gender was an enlightening read full of teflon-coated argument ammo, and The Undercover Economist had some interesting points but assumed I agreed with its central arguments a bit too much for my fucking liking, ta. Oh, and the only book on the list that I read for the second time was Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens, which I put down the first time absolutely convinced that he’d got a load of basic facts wrong. It turned out that he hadn’t, I was overexaggerating in my mind, and it was actually a fun read even on the second go. Sorry, Yuval.

I’m always interested in what high-performers in disparate fields do, and Tommy Caldwell’s Push was a brilliant insight into the effort – and setbacks – that go into being, genuinely, the best in the world at a thing (in this case, free-climbing El Capitan’s Dawn Wall). Dan Hardy’s Part Reptile is a smart reminder that the best people are often good at applying themselves to other things (commentary and fight analysis, say, but also some of the DMT/ayahuasca riffs that came earlier in Stealing Fire), and Michael Gibney’s Sous Chef a super-readable take on the expertise and thought that goes into a very different field. Jack Slack’s Notorious was less exciting because it’s pretty much a straight bio of Conor McGregor with some fight tips, but Candice Millard’s River Of Doubt, taking on a little-known period of Teddy Roosevelt’s ridiculous life, was a straight-up swashbuckler full of meticulous research and spit-take tales of derring-do. Very recommended.

There were three fiction books that I read in less than 24 hours each this year, and Naomi Alderman’s The Power was the best: a wrenching perspective-shift that starts with a smart premise (what if women were the overpowered gender, instead of men?) then delivers on it near-flawlessly. Second place was Home Fire, a book which you should endeavour to read entirely spoiler-free so I’ll shut up now, and third was Nic Pizzolatto’s Galveston, which is exactly the blend of booze-ruined characters and hardscrabble storytelling you’d expect from the man behind True Detective. Other books I blazed through just as fast as I fucking could included Budd Schulberg’s The Harder They Fall, a wisecracking tumble through the dirtiest era of boxing and The Contortionist’s Handbook, a breathless belter that felt more Chuck Palahniuk than most of Palahniuk’s own recent stuff. Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad was an absolutely searing read – awful, brutal stuff on an era I know shamefully little about – and Graeme Macrae Burnet’s His Bloody Project was a decent enough couple of hundred pages on serf-era Scotland…followed by another couple of hundred that probably seemed cool to people who haven’t heard of Rashomon. Maybe I just didn’t get it.

[Takes deep breath]

Somewhere in the summer a friend of mine recommended Gavin DeBecker’s The Gift Of Fear and Rory Miller’s Conflict Communication, both of which are full of game-changingly good insights: DeBecker on avoiding everything from assault to stalking and Miller on having more productive conversations with bosses, relatives and violent criminals – though not necessarily in that order. I liked the second one so much I ended up in a rabbit-hole of Miller books – Meditations On Violence and Training For Sudden Violence are both worth your money/time – and then graduated to his recommended reading, knocking off serial-killer memoir Whoever Fights Monsters (fine), criminal mindset primer Beggars And Thieves (okay) and seminal ‘violentisation’ investigation Why They Kill (banger) in short order. While we’re talking criminality I also read A Burglar’s Guide To The City, which was more like a collection of essays than a book and therefore only intermittently interesting: and then I started a new website, which you should definitely look at if you haven’t already.

By then it was October, and since my first Halloween read (Sarah Lots’ Day Four, which was completely fine until an ending that somehow retroactively made the rest of the book worse) was a dud, I went back to Shirley Jackson with The Haunting Of Hill House, a deservedly stone-cold classic featuring the best description of an evil building you’ll ever read. JD Vance’s controversial Hillbilly Elegy introduced me to a subset of America I didn’t know much about, Ta Nehisi Coates’ lyrical, brilliant Between The World And Me reminded me that there’s a whole world of bullshit that never even touches me (I also read his run on Black Panther, but that’s a graphic novel so I’m not counting it) and then the perfect jab-hook combo of Chimamanda Ngozi Achie’s We Should All Be Feminists and Katie Anthony’s Feminist Werewolf reminded me a couple more times. Benjamin Lorr’s Hell-Bent made a late-but-unsuccessful bid for the top ten: a non-stop spin through the mad world of Bikram yoga that wears its David Foster Wallace influence like a fancy hat. With the nights coming in I saw off Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology at a brisk clip, and read The Little Prince to the baby (he didn’t get it). I saved Robert Sapolsky’s magisterial Behave for the end of the year, because though it’s 800 pages long (including several appendices on intricate bits of biology that he insists you read), it’s every bit as brilliant as all of his other books, just as good as I hoped it would be, mixing science, anecdote and whimsy with a self-deprecating style and clear love of the subject that’s just a joy to read. Also: he thanks his research assistants in the footnotes, which seems like the behaviour of a very nice man.

Phew.

The top ten? Okay, these are the ones that I suggest you read: not necessarily the ones that I enjoyed the most (you’ll have to pick those out of the mega-post), but the ones that I think are the most life-changing for readers of Live Hard. In order, then:

- Conflict Communication

This was the book that made me realise I used to spend a lot of time talking to my team and my bosses wrong, even when I thought I was pretty good at it. You’re probably doing it too.

- Home Fire

A kick in the brain of fiction-as-empathy, which all of the publicity material does its best to spoiler for you. Just buy it and read it with no more ado.

- Selfie

Will Storr’s intellectual curiosity comes blasting through every page of this, and it’s just endlessly fascinating. Will read again.

- Tiny Beautiful Things

A book of advice columns? Listen, buddy: you’re not too good for advice columns. Get this one, and improve your life.

- Moonwalking With Einstein

Want a superpower? Reading this book feels like it gives you a superpower. (Into The Woods does too, but you don’t want the superpower of spoiling-all-films-for-yourself, trust me).

- Tribe

Honestly, this should say ‘Everything by Sebastian Junger’, but this one’s the most universal (and the shortest). Read it immediately.

- The Gift Of Fear

I’ve recommended this book to every lady I care about, and you ought to read it too. Turns out I would’ve been terrible at dealing with a stalker.

- The Power

A book that takes its elevator pitch and sprints with it, zig-zagging occasionally to stiff-arm your tidy ideas about gender straight in the face. Glorious and terrifying.

- Black Wave

I’m still not even sure what happens in this book, but sometimes I still chuckle about how much fun it was to read.

- Behave

Robert Sapolsky on top form, in a consideration of our best and worst behaviours that’s occasionally challenging but always entertaining. I love Robert Sapolsky.

Next year: I’m going to do one book-update post a month, because honestly doing it all at once is insane. Read hard!

HOMEWORK: Read one of the top ten this week.

Ooo! Thanks, Joel! I’ve read several and have a few to-be-read (you’re making want to set them out to be next in line). You’re impressive, meeting your goal and sharing all at once!

I missed the author of Conflict Communication. Who is it, please?